The Tongue Map: Tasteless Myth Debunked

By

Christopher Wanjek

LiveScience's Bad Medicine Columnist

The

notion that the tongue is mapped into four areas-sweet,

sour, salty and bitter-is wrong. There are

five basic tastes identified so far, and the entire

tongue can sense all of these tastes more or less

equally.

As

reported in the journal Nature this month, scientists

have identified a protein that detects sour taste

on the tongue. This is a rather important

protein, for it enables us and other mammals to

recognize spoiled or unripe food. The finding

has been hailed as a minor breakthrough in identifying

taste mechanisms, involving years of research

with genetically engineered mice.

This

may sound straightforward but, remarkably, more

is known about

vision

and hearing,

far more complicated senses, than taste.

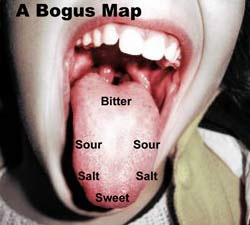

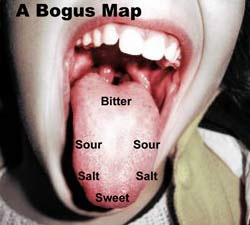

Maps

like this have been around for ages. But they

are wrong.

LiveScience Bad Graphic. Image: stock.xchange

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Only

in recent years have taste receptors been identified.

One of the first breakthroughs in taste research

came in 1974 with the realization that the tongue

map was essentially a century-old misunderstanding

that no one challenged.

You might know the map: The taste buds for

"sweet" are on the tip of the tongue;

the "salt" taste buds are on either

side of the front of the tongue; "sour"

taste buds are behind this; and "bitter"

taste buds are way in the back. Wineglasses

are said to cater to this arrangement.

The tongue map is easy enough to prove wrong at

home. Place salt on the tip of your tongue.

You'll taste salt. For reasons unknown,

scientists never bothered to dispute this inconvenient

truth.

The map has frustrated many a grade-schooler,

including me, who couldn't get the experiment

right in science class. I failed for insisting

I could taste sugar in the back of my tongue.

In fact, there's more to taste than sweet, sour,

salty and bitter. Most scientists agree

that there's a fifth distinct taste, called umami,

identified by a Japanese scientist named Kikunae

Ikeda in the early 1900s (and ignored by the West

for most of the twentieth century). This

is the taste of glutamate. It is common

in Japanese foods, particularly kombu, a type

of sea vegetable similar to kelp, and in bacon

and monosodium glutamate (MSG), which Ikeda isolated

and patented. There's considerable debate

about the existence of a sixth taste receptor

for fat, too.

The tongue map dates back to research by a German

scientist named D.P. Hanig, published in 1901.

Not familiar with Japanese cuisine, Hanig set

out to measure the relative sensitivity on the

tongue for the four known basic tastes.

Based on the subjective whims of his volunteers,

he concluded that sensitivity to the four tastes

varied around the tongue, with sweet sensations

peaking in the tip, etc. That's all.

In 1942, Edwin Boring, a noted psychology historian

at Harvard University, also apparently unfamiliar

with Japanese cuisine, took Hanig's raw data and

calculated real numbers for the levels of sensitivity.

These numbers merely denoted relative sensitivities,

but they were plotted on a graph in such a way

that other scientists assumed areas of lower sensitivity

were areas of no sensitivity. The modern tongue-map

was born.

In 1974, a scientist named Virginia Collings re-examined

Hanig's work and agreed with his main point:

There were variations in sensitivity to the four

basic tastes around the tongue. (Wineglass

makers rejoiced.) But the variations were

small and insignificant. (Wineglass makers

ignored this part.) Collings found that

all tastes can be detected anywhere there are

taste receptors-around the tongue, on the soft

palate at back roof of the mouth, and even in

the epiglottis, the flap that blocks food from

the windpipe.

Later research has revealed that taste bud seems

to contain 50 to 100 receptors for each taste.

The degree of variation is still debated, but

the kindest way to describe the tongue map is

an oversimplification. Why textbooks continue

to print the tongue map is the real mystery now.

As for the myth that the tongue is the strongest

muscle in the body, this doesn't seem to be true

by any definition of "strength."

The masseter, or jaw muscle, is the strongest

due its mechanical advantage, in which the muscles

attach to the jaw to form a lever. The quadriceps

and gluteus maximus have the highest concentration

of striated muscle fibers, a pure measure of strength.

The heart is the strongest muscle if you measure

strength as continuous activity without fatigue.

The tongue, on the other hand, wears out quickly-at

least with some people.