Life

is a Devil's Bargain: Cancer or Aging

By

Ker

Than

LiveScience Staff Writer

Deterioration

of body and mind are the prices our bodies pay for

protection against

cancer

as we grow older, new studies suggest.

Scientists have discovered that a gene

involved in tumor suppression also plays an important

role in determining when certain cells in the body

cease multiplying and

start

deteriorating. As cells age, the gene,

called p16INK4a, becomes more active. The cells

have greater protection against cancer but lose

the ability to divide. Cells that don't divide die

off and are not replaced.

The studies, detailed together in the Sept. 7 issue

of the journal Nature, suggest the physical and

mental

ravages that accompany aging

are not the result of simple wear and tear of the

body, but of a cellular decline that is programmed

into our genes-one designed to safeguard us against

copying mistakes that become more frequent as we

grow older.

"This research tells us why our old tissues

have less regenerative capacity than young tissues,"

said Sean Morrison of the University of Michigan,

who was involved in one of the studies. "It's

not that old tissues wear out-they're actively shutting

themselves down, probably to avoid turning into

cancer cells."

No free lunch

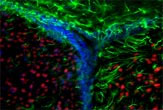

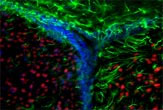

Research teams from three medical schools examined

the role of p16INK4a in cells collected from different

parts of the body in mice.

One team, from the University of North Carolina

(UNC) at Chapel Hill, looked at the gene's role

in pancreatic islet cells, which produce and secrete

the hormone insulin

and which are defective in persons with Type 1 diabetes.

Another team from the University of Michigan examined

brain stem cells while a third, from

Harvard University, looked at p16INK4a in blood

stem cells.

All three studies found similar results: as animals

got older, p16INK4a activity increased and the cells

eventually stopped dividing. Cells in mice deficient

in the gene continued to divide but were more likely

to turn cancerous, while cells in animals with over-expression

of the gene stopped dividing earlier and aged prematurely.

The experiments also showed that cells taken from

old animals remember their "age" and continue

to deteriorate at their previous rate even when

transplanted into young animals.

This last finding raises new questions about the

usefulness of adult

stem cells in tissue and organ repair

compared to embryonic

stem cells.

Fresh debate

The use of embryonic stem cells in medical

research is currently a topic of

fierce

debate because harvesting the cells destroys

developing embryos. As an alternative,

some scientists are trying to use stem cells taken

from adults and grow them into tissues in the lab;

the new cells could then be reintroduced into the

patient's body to replace failing tissues or organs.

"I think this data undermines that notion,"

said Norman Sharpless, a researcher at the University

of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill who was involved

in all three studies. "It shows that even these

[adult] stem cells, which have the properties of

self-renewal, are not limitless in their capacity

to regenerate themselves. There are tumor-suppression

mechanisms that limit their longevity."

Not all of the researchers agree. Morrison, the

University of Michigan researcher, doesn't think

the findings will have a drastic impact on how doctors

use stem cells.

"I don't think this is a reason to say that

embryonic stem cells are more valuable that adult

stem cells," he said in a telephone interview.

"It's been recognized for a long time that

young adult [stem] cells are more robust than old

ones. For example doctors are reluctant to do bone

marrow transplants when the donor is old."

The more important consequence of the new findings,

Morrison said, is that it helps explain embryonic

stem cells seemingly limitless ability

to divide and become new cells.

These tumor-suppression "mechanisms probably

don't exist in embryonic stem cells, and that's

why they can proliferate indefinitely, while adult

stem cells can't," he said.

Potential uses

The findings could prove to have numerous practical

uses as well, the researchers say. For example,

p16INK4a could be used as a "biomarker'

to determine a cell's age. It is "like an odometer

almost-you can use it to tell the mileage of the

tissue," Sharpless told LiveScience.

This could allow doctors to one day do things like

sort blood stem cells based on physiological age

to determine whether someone will be a good bone

marrow donor or not.

Also, it might be possible to create drugs that

temporarily inactivate p16INK4a and promote healing

in damaged cells, Morrison said.

"We could give people who have injuries a drug

like that for a week or two weeks or a month,"

he said. "That's not likely to cause cancer,

and even if some cells started to divide a little

out of control during that period, you just stop

the drug and p16INK4a comes back on and shuts things

down again."

The findings might also lead to new kinds of therapies

aimed at slowing

or reversing the effects of aging, the

researchers say. In the experiments, shutting down

p16INK4a activity relieved only some, but not all,

of the negative repercussions of aging. But scientists

know of other tumor suppressor genes, and manipulating

many of them at once might have a greater effect,

Morrison said.

"Maybe if we look at the aggregate effects

of five or six different tumor suppressors, we might

be able to rescue most

|